PERSISTENT IDENTIFIERS:

COMMERCIAL AND HERITAGE VIEWS

2/9 – Mistaken identity: a fictional case study

Summary

“Identifiers in the Commercial World” introduced the idea of a supply chain made up of organizations with different roles in creating and selling a media product. Product identifiers are the key to communication along that chain.

Here we offer a fictional and fun “case study” to help you understand some of the practical ways identifiers are used at each step of the supply chain. This should make the ideas in the real case studies clearer.

Intended audience:

- library and information professionals & masters students

- heritage (museum, archive, gallery) professionals & masters students

Learning outcomes – readers should aim to:

- understand how persistent identifiers work in practice in the commercial sector, and how that might apply in heritage work

- know why metadata has to be assigned to each identifier.

Page Index

Finding John Williams

What’s in a namespace?

Making the right connections

Does all this apply to heritage organisations?

Is everything relative?

Finding John Williams

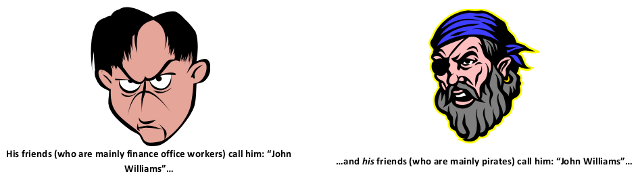

Imagine you are a police officer, sent to find someone called John Williams. Your sources say he has stolen a large amount of money. You need to identify him and bring him in for questioning.

Files on two suspects have been brought to you. Can you identify John Williams from the two police artists’ sketches and notes below?

You need to ask for more information on the “John Williams”: do they want…

- Mr. John Williams, the finance office worker?

- or Captain John Williams, the pirate?

What’s in a namespace?

A person’s name is a useful for finding that person – but only if there is only one “John Williams”! This is the problem of uniqueness and it depends on context.

Outside the contexts of the police investigation and the suspects friends, there could be thousands of people called “John Williams”. A personal name is not universally unique.

The context in which a name or identifier for something or someone is unique is the “namespace” (OK, this is actually a very specific term in computer science, but the basic idea is similar).

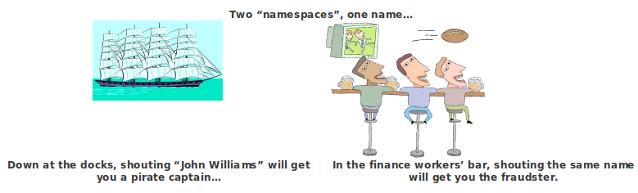

Asking for John Williams by the same “name” in the contexts of the two

sets of friends – the “namespaces” below – will get two different

results. In the context of the investigation, that includes both groups,

you can specify both the “local” name and the “space” where it applies.

A phonebook might be an example of a “good namespace” in which you expect to find one and only one person referenced by each “name”.

Each phone number is the “unique name” or identifier of that household or business. Note that it is the phone numbers that are unique names, not the names of the people. The phone numbers identify telephones that you may call, not people (there will often be more than one actual person with the same name, and one person may have more than one phone).

These examples hint at the fact that any system of unique identification needs a human element, a social and organisational component to maintain it.

This identifier agency must have a public face, to present it to the world at large and its users so they know which namespace they are dealing with.

Making the right connections

You send officers to find both suspects. The two men might be out alone, so could not be recognised by their friends at the finance office or on the treasure ship.

What identifying characteristics could you give to your officers? Perhaps the file might look like this:

| Differentiating number | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Male |

| Typical facial expression | Angry | Angry |

| Hair colour | Black | Grey |

| Head wear | None | Pirate bandana |

| Eye wear | None | Eye patch (right eye) |

| Jewellery | None | Earring (left ear) |

| Facial hair | None | Beard and moustache |

As your officer sees each of these characteristics, he becomes more certain that this is the correct “John Williams”. These are the “metadata” for each suspect that enable the activity of identification. They are even more important for computer systems, which are unable to pick up other “clues”.

But – for a case with hundreds of suspects, how could your officer quickly and accurately report which suspect they have seen?

Using a unique identifier!

This is a good idea, for the same reasons as we discussed in “Identifiers in the Commercial World”. What would the identifier code look like?

A structured identifier for each person like “2013-case-1-name-j-williams-number-1” might be highly unique, and might make your filing system easier to organise.

Some problems might be:

- what if you need to share those files and their identifiers with police in other places, and you want to protect the privacy of suspects who, after all, might not be the John Williams you are looking for?

- what if some of the known details change, for example, the spelling of Williams’ surname is found to be in fact “William” without the “s”, when discovered in writing for the first time? Would referring to the suspect using an identifier built on the old information cause confusion? Or perhaps you might discover “William” to be a pseudonym?

An dumb number like the simple serial number above – with the namespace “Suspect number” – would be more appropriate:

- Extra “linking” details, like the year, the case number and the suspect’s name, characteristics and differentiating number can be held in a separate, confidential file.

- They would be shared only with the appropriate agents, at the right time and place. Information that changes a lot, like spellings or even whole names, could then also be shared only after the latest update.

- Dumb numbers like these are also easier to transmit in various ways since they contain fewer details that can be mis-heard or mis-read.

- A number could include a little structure relating to the namespace e.g. part of the number might indicate the location of the police station where the file was first created.

- It could incorporate a check digit based on a defined mathematical formula which would help to recognise mistakes in transcription and transmission.

If a new officer takes over these files, using a “dumb” serial number to identify each suspect’s file will avoid confusion.

- An identifier structured with details of when the file was created, by whom, and what the “linking information” was thought to be at the time. In this way the new officer would not be drawn into thinking that such details were still the latest news.

What if new details of a known, identified suspect come in? Maybe a new witness tells you that suspect 0000-0000-0001 actually has blond hair and glasses?

- There must be some management processes to keep other police services up to date with changes to the files, and perhaps select between alternative reports on the basis of how much you trust the information source;

- To look up these suspect numbers and get accurate information, agents on the ground will need to know who maintains the files, and have some mechanism for contacting the authorised holder of the information to retrieve it.

Commercial sector identifiers in real life use all of these features.

Does all this apply to heritage organisations?

This fictional, highly exaggerated example, highlights some of the problems that identifier systems in the commercial and heritage sectors are expected to solve.

In the real world, cultural heritage professionals and information managers in the creative industries deal with ambiguity and complexity on a very large scale, especially in the Web environment.

For example, Wikipedia lists several “artists and entertainers” known as John Williams 1

| Full name(s) | Profession(s) | Earliest date | Latest date |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Williams | Stage, film, and television actor | 1903 | 1983 |

| John Williams | Classical guitarist | 1941 | |

| John Williams | Composer | ||

| John Williams | Radio personality | 1959 | |

| John A. Williams | Novelist | 1925 | |

| John B. Williams | DJ | 1977 | |

| John David Williams | Musician and songwriter | 1946 | |

| John Edward Williams | Author of novels | 1922 | 1994 |

| John Ellis Williams | Novelist | 1924 | 2008 |

| John H. Williams | Film producer | ||

| John Hartley Williams | Poet | 1942 | |

| John James Williams | Poet | ||

| John McLaughlin Williams | Conductor | ||

| John Richard Williams | Poet | 1867 | 1924 |

| Johnny Williams | Blues guitarist | 1906 | 2006 |

| Johnny Williams | Jazz drummer | 1905 | 1984 |

| J. Lloyd Williams | Botanist, author, and musician | 1854 | 1945 |

In most of these cases, seeing the profession and vital dates of people with similar or the same name is enough to tell them apart; the larger database of ISNI (International Standard Name Identifier) lists 85 “creators” called John Williams, and in the Web environment of course the number of documents containing this common name may increase to thousands or millions.

Putting together a comprehensive online guide to “John Williams”, or making a new exhibition or publication on “John Williams” stand out in this crowd will need a lot of work!

Is everything relative?

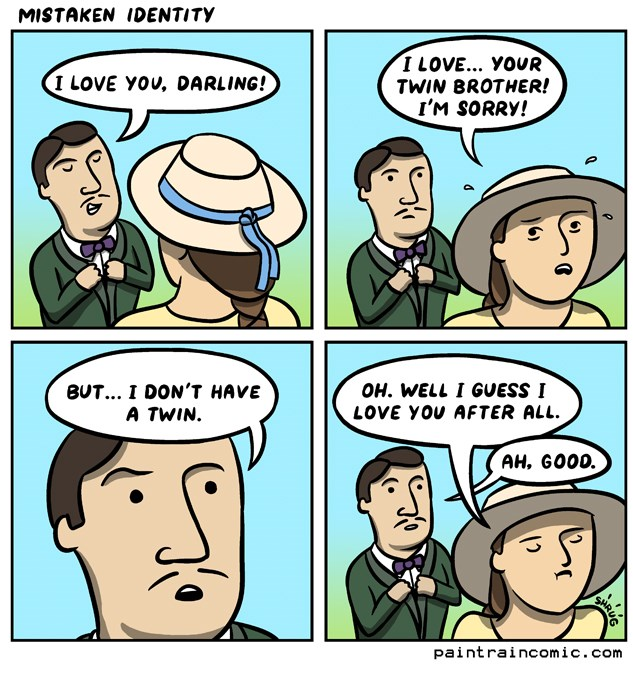

A word needs to be said here about the meaning of “identity”.

In the police story above, “identity” is a requirement for similarity in every possible way. There can be only one “right” criminal in the end. Jailing a John Williams who is “relatively similar” to the one who actually stole the money in question is not acceptable.

Many situations involving personal identity require absolute identity: e.g. curation of an exhibition on John Williams, or publication of one of the poet John

Williams’ poems. This is the type of “identity” we are most familiar with from daily life:

2

In the cultural heritage world, absolute identity is the normal goal of maintaining data and identifiers.

Visitors to a Pelé football museum expect to see the footballs used by Pelé, not just “a” football of a similar type, or perhaps the shirts worn by him during his World Cup winning matches, not just “a” shirt produced for his team.

- Heritage objects, even when many similar items exist, take on some of the “personality” of the events, things and people they are associated with:

Those unique events can only have happened to one specific thing – museum objects are not substitutable.A museum object is more like an illustration or witness of the past, than information in its own right. 3

- In contrast, commercial products, especially media products that

convey information, rather than “history”, are intended to be only relatively

identical – that is, they are functionally identical:

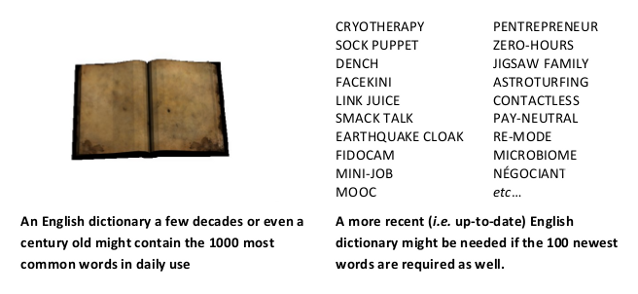

For example, a request for “an English dictionary” for the purpose of learning the 1000 most common words for daily conversation may be satisfied by even very old editions. But to for the purpose of learning the latest jargon and buzzwords on the Internet, this “English dictionary” may not be identical after all:What is "the same thing" ("a copy") for one user, purpose, or context will be "two different things" for another. The two users may have different purposes in mind when they ask "are X and Y the same?"; and as we have seen, this question is implicitly "are X and Y the same for the purpose of...?" 4

A dictionary of “English” – and a dictionary of “the latest English”

We highly exaggerated the differences in user requirements for each English dictionary. But we are talking about at least two different products.

Commercial sector identification can be complex because differences between two similar products become smaller and smaller, but still make a great difference to everyone involved, from photographers, the authors of books and film scripts, and composers of music, to the eventual purchasers and readers, listeners and viewers.

The cultural heritage “view” focusses on “this item”:

| Particular item | Identification | Other “copies” | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelé’s World Cup winning football shirt |  | http://pele-world.museum/objects/00000000001 Unique interest; no substitutes possible | None possible. Each shirt considered unique due to its associations; even if otherwise very similar style, material etc. |

| John Hartley Williams’ work shirt |  | http://j-hartley-

williams.museum/objects/00000000001 Unique interest; no substitutes possible |

|

| John James Williams’ work shirt |  | http://j-j-williams.museum/objects/00000000001 Unique interest; no substitutes possible |

|

In the commercial world, the focus is on “this product” – which really refers to a “set” or “class” of identical items. If there are three copies of a new book in the bookshop, it does not matter at all which of the three you buy - they are identical.

The real value in media products is some unique intellectual property. Intellectual property by its nature can be reproduced, hence the importance of copyright law:

| Particular product | Identification | Other copies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old (but cost-effective) English dictionary |  | This product: ISBN 978.....1 (any copy is good as another) |    ...probably limited number (it may be “out of print”) ...probably limited number (it may be “out of print”) |

| New English dictionary (published 2013) |  | This product: ISBN 978.....2 (any copy is good as another) |   ...probably

possible to order more (in print) or even request new copies (print on

demand) – or permanently available (e.g. as an ebook) ...probably

possible to order more (in print) or even request new copies (print on

demand) – or permanently available (e.g. as an ebook) |

| Not so new English dictionary (1997) |  | This product: ISBN 978.....3 (any copy is good as another) |   ...probably

still available for sale but not necessarily “in print” or even

available as an ebook; far less demand for slightly older dictionaries

than for “the latest”! ...probably

still available for sale but not necessarily “in print” or even

available as an ebook; far less demand for slightly older dictionaries

than for “the latest”! |

Of course there are some grey areas, for example, museums of ephemera or popular culture, rare book dealers, or a publisher who deliberately issues limited editions of a fixed number of copies, and maybe other more unique features, like the author’s signature 7:

Identifier Interoperability: A Report on Two Recent ISO Activities by Norman Paskin; DLib, 2006.

A technical paper explaining the importance of a minimum set of metadata attached to any identifier so that it can be used in practical applications.

Indecs metadata framework (PDF), by Godfrey Rust and Mark Bide; 2000.

A comprehensive technical guide to commercial sector metadata principles, including creation of identifiers.

NOTES

1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Williams_%28disambiguation%29 ↑

2 Mark Pain © http://paintraincomic.com/mistaken-identity/ ↑

3 http://www.researchspace.org/researchspace-concepts/technological-choices-of-the-researchspace-project ↑

4 http://www.dlib.org/dlib/january03/paskin/01paskin.html ↑

5 http://32cherry.deviantart.com/art/book-264579890 ↑

6 http://dictionaryblog.cambridge.org/tag/neologisms/ and http://dictionaryblog.cambridge.org/tag/neologisms/page/2/ ↑

7 http://www.worldheadpress.com/special-editions-231 ↑